As Sri Lanka’s army corners Tamil Tiger rebels in a tiny sliver of land, the next test for the government lies in how it deals with the mass exodus of humanity from the war zone.

As Sri Lanka’s army corners Tamil Tiger rebels in a tiny sliver of land, the next test for the government lies in how it deals with the mass exodus of humanity from the war zone.

The army says more than 80,000 people have fled the area in the past two days – a figure that already exceeds the government’s earlier estimates of the number of civilians trapped.

Estimates of the numbers left inside vary from 30,000 to 120,000 people – but conditions for them have been described as "nothing short of catastrophic" by the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross).

The rebels and the army have accused each other of killing civilians in recent confrontations.

Those that escaped have made a harrowing journey, navigating swampy territory, carrying their belongings and wading through a lagoon until they reach military checkpoints on the other side.

They are processed at these checkpoints, they are taken to reception centres at Omanthai and from there, eventually, to internally displaced people (IDP) camps in the dry, arid district of Vavuniya.

Shelter ‘crisis’

But there are questions about how so many people can be housed adequately in such a short time – and how long they will have to stay there.

But there are questions about how so many people can be housed adequately in such a short time – and how long they will have to stay there.

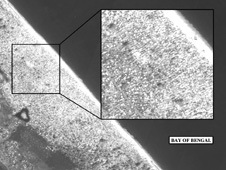

Many civilians have been arriving from the war zone by sea

"A huge influx of people like this means you are going to have a crisis, especially in an underdeveloped area like Vavuniya," says Tony Senewiratne, national director for Habitat for Humanity, a shelter organisation.

The government has cleared 900 acres of land for shelters and IDPs are also being housed in schools.

"If you can visualise a very dry area where temperatures rise to about 35C, it’s hot and humid, the ground has little shade. People are confined to small tents, tarpaulin or plastic. During the heat of the day it would be impossible to stay inside and there is no shelter outside," said Mr Senewiratne.

"It is going to be a difficult issue for anyone to solve quickly," he said, with part of his task to assess the building of transitional shelters.

‘Two year’ wait

Mr Senewiratne says that although aid agencies would like to see people resettled within months, it could take up to two years before IDPs are relocated.

"Therefore temporary shelters being put down on the ground are not adequate," he said.

"Therefore temporary shelters being put down on the ground are not adequate," he said.

This timescale is endorsed by Roshan Mendis, CEO of the Lanka Evangelical Alliance Development Service (LEADS), who adds that this is an ever bigger challenge than the tsunami.

"It could take anything up to two years. Look at the realities of the situation and how long it took us to put people back even after the tsunami, which didn’t have these political ramifications."

Mr Mendis says he has "fast-depleting resources to cope with the numbers" in the camp that his organisation manages.

They have 19 community kitchens which are run by the IDPs themselves, the most efficient way, he says, of managing the operation. As they are about to receive 5,000 more IDPs straight from the war zone, they are building more kitchens.

He also says conditions are poor: "When it rains, the ground has not been prepared with draining, so sections get flooded out. So conditions are not the best for the elderly and the children. A tent can have up to three family units and you do get cases of people not knowing each other living essentially in one tent," he said.

Another major concern for rights groups has been the lack of freedom of movement between camps. Families have been split up and, according to a statement by Medecins Sans Frontieres, [MSF] been unable to find any information about relatives who may be in other camps.

Mutthiahi Linganathan arrived in one of the camps three weeks ago and describes how he ran and crawled through the war zone to escaped the firing.

He told the BBC the toilets were working but there was a shortage of drinking water.

"They don’t allow us to meet our relatives. I have three sons studying in Vavuniya. I want to go and live with them. But here they don’t allow me even to meet them," he said.

The LTTE have described the units as "internment camps".

‘Feel safer’

Mr Mendis points out that while conditions might not be the best, "talking to people, they feel much safer here than they did where they were before".

And the government is confident it can provide for the latest IDPs streaming in from the war zone.

Minister for Rehabilitation and Resettlement Ameer Ali says the government has processed 74,000 people already and is in the process of accommodating 58,000 more.

"We have the capacity to look after them and their shelter. There is no problem at all. Whoever comes, we can accommodate. Altogether 120,000 IDPs have come and we are hoping that there are 20,000 to 30,000 more still inside the safe zone," he told the BBC News website.

He asserts that the government is eager to resettle people as quickly as possible.

(For updates you can share with your friends, follow TNN on Facebook and Twitter )