The disappeared come back to haunt the government in Colombo

As the international community observed the United Nations International Day of the Disappeared on August 30, four police officials in Sri Lanka were jailed for their part in disappearances.

As the international community observed the United Nations International Day of the Disappeared on August 30, four police officials in Sri Lanka were jailed for their part in disappearances.

Former Senior Superintendent of Police Douglas Peiris and three other police officers were found guilty at the Gampaha High Court of abduction of two young boys who were brothers, with the intention to kill, and were sentenced to five years rigorous imprisonment. This incident took place in 1989 in a period in which a large number of disappearances, estimated officially at 30,000, took place. Peiris and many other senior police officers have been accused of engaging in large-scale disappearances, but the prosecution of these cases has failed due to many factors.

The prosecution of this particular case has taken 20 years. Only a handful of cases out of the huge number of disappearances were prosecuted. Since 1991, the Sri Lankan government has formed nine ad hoc Commissions of Inquiry to investigate enforced disappearances and a number of other human rights-related inquiries. These commissions of inquiry have lacked credibility and have delayed criminal investigations, according to Amnesty International, which has accused the government of failing to protect victims and witnesses. While most, if not all, of these Commissions of Inquiry identified alleged perpetrators, very few have ever been prosecuted.

Most of the cases brought to court failed, usually due to witness intimidation or the natural deaths of witnesses due to the long delay. The investigations into the cases themselves started only many years after the incidents due to political pressure to protect the perpetrators. It was only after changes of governments and popular pressure that action was taken, though wholly inadequate, to investigate some of the cases.

Commissions of Inquiry into Forced Disappearances were appointed by the government several years after the incidents, and the mandate of these commissions were mostly of a fact-finding nature. However, many people turned to these commissions and provided extensive information of the manner in which the disappearances has taken place during this time. These witnesses also gave details of the perpetrators who were involved in the abductions, detentions, interrogations, torture, killings and disposal of bodies.

At the conclusion of their inquiries the Commissions submitted a list of persons against whom there was sufficient evidence to prosecute and where necessary to conduct further investigations in terms of the criminal procedure in Sri Lanka.

The list of these persons was submitted to the government and the Attorney General’s Department. However, in most of these cases no prosecutions or further inquiries were conducted.

The list given by the Commissions revealed that many of the persons named by them as having being identified for engagement in disappearances were still, and are still even now, in places of high political positions or in the police or military service.

Several governments which have come to power subsequent to the submission of these reports by the inquiring commissions have kept these reports secret. Thus, the credentials of these politicians and officers to hold these positions have never been challenged.

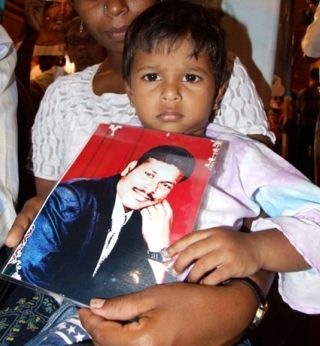

Disappearances in Sri Lanka mean killings after arrest. Many young persons were taken from their homes by police or military personnel and the families were promised that they would be safely returned after the recording of a statement. However, they were never returned and in many instances, within a short period their dead bodies were found in the streets.

It is a crime, both under Sri Lankan and international law to kill a person after arrest. Killing a person after arrest is different from killing in combat between rebels and the armed forces. Even in that instance, if someone surrenders or is taken into custody after being wounded, each side has an obligation to protect the life of such a person and, if necessary, bring them to justice. However, in Sri Lanka the killing of persons after securing arrest was done in a large scale. The case prosecuted before the Gampaha High Court, mentioned earlier, was about two young brothers, one of whom was 16 years of age. The Commissions of Inquiry into Forced Disappearances revealed that 15 percent of the cases of disappearances that were reported to the Commissions were of persons were 19 years of age or younger. Thus, of the 30,000 disappearances from the time, more than 4,500 persons were boys and girls below 19 years of age.

It was in the causing of these disappearances that an entrenched tradition was built within Sri Lanka to abandon the judicial process and to engage in extrajudicial killings whenever a government wished to do so. The disappearances in the late 1980s were the result of a deliberate government policy. This policy itself has never come before a public inquiry. The Commissions of Inquiry into Forced Disappearances provided enormous details of the disappearances of the time. These details reveal a well-designed policy carried out by the government, by the police, military and paramilitary groups, with full knowledge of the heads of the armed forces.

(For updates you can share with your friends, follow TNN on Facebook and Twitter )