Tamil Tiger rebels were crushed in Sri Lanka’s civil war, while President Rajapaksa from the Sinhalese majority has gone from strength to strength. His government is expected to win parliamentary elections on Thursday – and many minority Tamils now wonder what the future holds. The BBC’s Charles Haviland reports from Jaffna.

Tamil Tiger rebels were crushed in Sri Lanka’s civil war, while President Rajapaksa from the Sinhalese majority has gone from strength to strength. His government is expected to win parliamentary elections on Thursday – and many minority Tamils now wonder what the future holds. The BBC’s Charles Haviland reports from Jaffna.

The Nallur temple, a great Hindu shrine, is alive with drumbeats and the sound of squealing horns.

There are crowds of school students, including a flock of mainly Sinhalese visitors from the south-east.

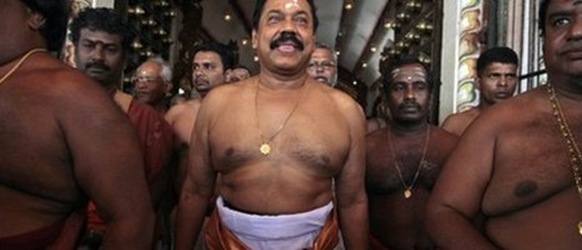

Sinhalese Buddhists are glad to be back in Jaffna after the war. Tamil Hindus welcome them. Hindu and Buddhist alike strip off their shirts to enter the temple and worship the popular deity Murugan.

Sinhalese Buddhists are glad to be back in Jaffna after the war. Tamil Hindus welcome them. Hindu and Buddhist alike strip off their shirts to enter the temple and worship the popular deity Murugan.

Local student Ramanan is here with three friends and, like others in the majority-Tamil city, he says life has improved with the end of the civil war.

But given that the Tamil Tiger rebels were defeated last May, he is annoyed by continuing restrictions.

"If the government thinks the Tigers are no longer there, why are there so many checkpoints?" he says.

"If they think the Tigers are no more, they must leave us alone. Just to come here from my place takes a long time because of all the checks."

‘Cultural vandalism’

People in the port city of Trincomalee, a little way down the coast, also say life is getting more relaxed.

But there was terrible violence in the recent past and, with many cases unresolved, people have a sense of grievance.

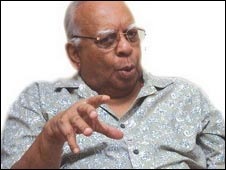

R Sambandan, a veteran politician who leads the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), lives and campaigns in Trincomalee.

His party was very close to the Tigers and remains the biggest and most popular Tamil political group.

Mr Sambandan alleges that Tamil culture here in the north-east is being threatened.

"Tamil Hindu religious places of worship have come under severe attack in the recent past," he says.

"There has been encroachment on places of cultural importance to us. There is an organised movement in the country which unquestionably is engaged in these deliberate acts of sacrilege and cultural vandalism."

The TNA has abandoned the Tigers’ old idea of a separate homeland for the ethnic minority.

In recent weeks, it has even jettisoned some of its former MPs seen as too hard-line.

But the Alliance still demands federalism or autonomy for Tamil-majority areas – the Northern and Eastern provinces – in order to "preserve and nurture" their Tamil-speaking cultural identity.

No minorities?

But whatever the grievances of Tamils, they may not automatically vote for the TNA.

President Mahinda Rajapaksa visited Jaffna last week to address a rally in a place which is politically difficult territory for him.

A Sinhalese from the other end of the island, he scored badly in the region in a recent presidential election.

With a small crowd in the stadium, he made an effort to address them in their language through an incredibly loud speaker system. They were loyalists and applauded.

His talk was not of political reforms but of development. What the Tamils want, he said, was schools, homes, a railway extension.

That is his continuous refrain these days: major development projects will heal the Tamil-populated areas; and that the country in fact has "no minorities".

Some see his message as an anti-discrimination plea, but others fear minority rights will get trampled on.

Even within the president’s own Sri Lanka Freedom Party, some take a distinctly different approach from that of Mr Rajapaksa.

Like all those standing for the party in Jaffna, K Sri Saravana Pavaan is Tamil. He told the BBC that his ethnic group does need special assistance.

He would like one-third of all state sector jobs to be reserved for Tamils and Muslims, whose mother tongue is also Tamil.

He also wants English to be the language of administration in the provinces where Tamils are in a majority.

Most people believe the president does not want any special treatment for those areas.

"That may be wrong," he says.

"Because we have been affected by the violence. Because we are disabled people. Normally a disabled person needs special treatment."

All-powerful president

Sri Lanka’s Tamils have an array of politicians competing for their votes. Some – including former paramilitary members – are now with the government but still, in many cases, feared.

Those close to the Tamil Tigers, like the TNA, win the votes of many but are despised by others for not having stood up to the rebels’ violence.

Then there are moderates struggling to have their voice heard. Many moderate Tamil politicians were killed by the Tigers.

Waiting at the Jaffna bus-stand, Mrs Vanaja Uma Khanta, who is in her 40s, says none of the Tamil politicians is quite right for her.

"We’ve faced so many problems because we Tamils didn’t have proper leadership," she says.

"Only when we have a good leader who’s experienced and who understands Tamils’ problems, and will fight for our rights, can our problems be solved."

The coming election is likely to make President Rajapaksa more powerful than ever – and his word is what counts.

The federalism that the TNA campaigns for, as well as the positive discrimination some of the president’s own party colleagues desire, may be forlorn hopes as long as the president does not want them.

(For updates you can share with your friends, follow TNN on Facebook and Twitter )