In a small town in Mannar, a commemoration ceremony was being held. The town had been heavily bombed during the war. Perhaps the priest thought the people would benefit from closure, perhaps it was a reminder of how much they had gained now that the war was over. Whatever the reason, the ceremony was interrupted by police.

In a small town in Mannar, a commemoration ceremony was being held. The town had been heavily bombed during the war. Perhaps the priest thought the people would benefit from closure, perhaps it was a reminder of how much they had gained now that the war was over. Whatever the reason, the ceremony was interrupted by police.

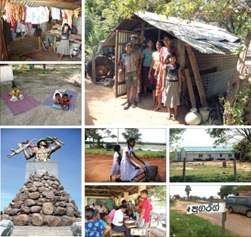

At a glance, Calleigh McRaith could be any other tourist. She is actually part of a group of law students from the University of Virginia, here to conduct their research projects. Until recently, the North and East were off-limits to foreigners, unless they could manage to get Ministry of Defence clearance. That has changed, and Calleigh visited rural Mannar to speak to people there. Doing so gave her a unique perspective into people’s problems, post-war. With reassurances that their identities would be protected, people opened up to Calleigh about their problems.

Not being able to mourn the dead was one thing they spoke of. In some cases, of course, it was less black-and-white; some of the names painted over were LTTE rebels, killed in combat.

People there were angry about the LTTE and their methods, especially the forced conscription, Calleigh says- but they also said that the struggle towards reconciliation was uneven for many.

Calleigh’s travels put her in touch with many people on the East coast, including former LTTE members who had undergone rehabilitation in the camps. Here, people who had been in the LTTE for 20 years could theoretically be released from the rehabilitation camp in one year. That’s not a long time to unlearn an ideology. But the sentences are skewed, on a case-by-case basis. One woman had worked two years in an LTTE office, and remained in a rehabilitation camp for two years. That might seem like a fair sentence, but consider the man who served as a watchman for 10 days, and who also served two years in the camp.

Or the two young girls who were recruited into the LTTE as children, but were over 18 when they entered rehabilitation. They were tried as adults, and one girl who spent three months as a simple labourer spent over a year in the camp. Of the people who took amnesty in one of the Mannar camps, just three had received formal training, people of the area told Calleigh. All the others had been put to work cultivating patches of garden and working in the jungle.

Calleigh spoke to Government officials who claimed that those who had no formal training in the LTTE were released earlier, but this was not the reality as she saw it.

In addition, the livelihood training was sometimes fruitless. Two former LTTE members, one a labourer, the other an office worker were given courses in sewing and beauty culture. Neither of them was able to secure jobs afterwards.

Between this and the hours of interrogation, the duo often thought that the years spent had been wasted.

Meanwhile, there are still people missing. Calleigh encountered a woman who had lost her husband and daughter. While witnesses had seen her husband in a rehabilitation camp, no one was willing to come forward and go to court, and so the wife was losing hope of ever finding her husband.

Those who did leave Menik Farm found themselves facing innumerable land issues, with the Government taking over plots of land in some cases, preventing families from returning home. One person saw his house looted and destroyed within days.

“The Army is allowing people to do this. We don’t have anything to go back to,” he told Calleigh.

The result, as activists in Jaffna told Elizabeth Dobbins, another student, was an extreme fear of those in the military, partly because of the language barrier. The view was that the rule of law was so disintegrated that the police could shoot to kill, with no accountability.

(For updates you can share with your friends, follow TNN on Facebook and Twitter )