“Tamil Imprints in New Zealand” by 87-year-old Eezham Tamil author A.T. Arumugam, now living in New Zealand, re-documents and discusses in detail a bronze bell inscribed in Tamil in c. 14-15 century writing that was in the possession of the native Maori people of New Zealand. Originally written in 2007 in Tamil, the book has been translated into English and will be released shortly in Wellington. The publication is sure to give a sense of pride and belongingness, and would contribute to integration with identity for the Tamils of New Zealand today, commented a social worker. Meanwhile, reviewing the book, V. Sivasupramaniam, who also contributed to the translation says, “This book of fifty-two pages could provide a good incentive for historians and researchers to go further deep into the migratory pattern of this multi-cultural country.”

“Tamil Imprints in New Zealand” by 87-year-old Eezham Tamil author A.T. Arumugam, now living in New Zealand, re-documents and discusses in detail a bronze bell inscribed in Tamil in c. 14-15 century writing that was in the possession of the native Maori people of New Zealand. Originally written in 2007 in Tamil, the book has been translated into English and will be released shortly in Wellington. The publication is sure to give a sense of pride and belongingness, and would contribute to integration with identity for the Tamils of New Zealand today, commented a social worker. Meanwhile, reviewing the book, V. Sivasupramaniam, who also contributed to the translation says, “This book of fifty-two pages could provide a good incentive for historians and researchers to go further deep into the migratory pattern of this multi-cultural country.”

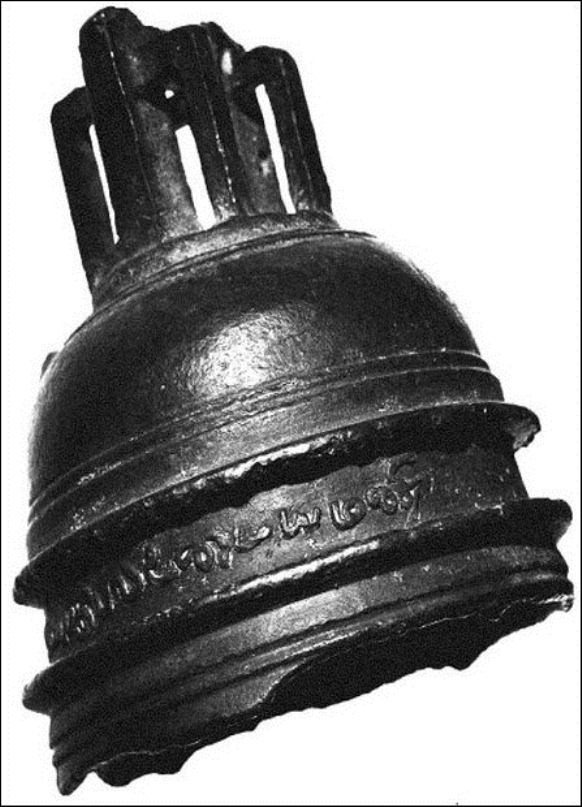

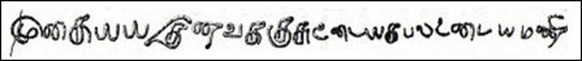

The bell with Tamil inscription of c. 14-15 century CE, found in New Zealand. The legend should be read by applying single consonants in the following way: mukaiyya theen vakkuchu udaiya ka[p]pal udaiya ma’ni.

The bronze bell that bears the inscription in Tamil, reading, “Mukaiyyatheen Vakkucu Udaiya Ka[p]pal Udaiya Ma’ni” means “the bell belonging to the ship belonging to Mukaiyyatheen Vakkuchu.”

“முகைய்ய தீன் வக்குசு உடைய க[ப்]பல் உடைய மணி”

The bell was originally fixed to a ship owned by a Tamil-Muslim seafarer (Mohaideen Baksh) that probably reached the shores of New Zealand.

The find not only implies Tamil maritime connections with pre-colonial New Zealand, but also evidences naturalisation of Islam into Tamil heritage.

Even though the archaeological find was discovered as early as in 1836 by the missionary William Colenso who was working with the Maori people, the early connections Tamils had had with New Zealand was unknown to today’s Tamil world until the find was brought to limelight by the Eezham Tamil scholar Rev. Fr. Xavier Thaninayagam. The publication of Mr. Arumugam is aptly dedicated to the memory of Fr. Thaninayagam.

Born in 1925 at Punnaalaik-kadduvan and grew up in Thellippazhai in Jaffna, Mr. A.T. Arumugam served as a teacher and later as principal of various schools in the island. In 1996, while retired and living in I’lavaalai in Jaffna, he was displaced by the civil war and migrated to New Zealand with his family.

* * *

Review of the book by V. Sivasupramaniam

“Centuries old bell with lettering in Tamil exhibited in the New Zealand museum in Te Papa, Wellington and brought out to International attention by the reputed Tamil scholar and researcher of Sri Lanka, Rev.Father Thaninayagam evoked my interest to do further research into the antiquity of the bell and the Tamil migration to New Zealand,” says the author, Mr A.T.Arumugam of “ Tamil Imprints in New Zealand” published in Wellington in Tamil in 2007 – the translation of it in English will be released shortly in Wellington.

Mr Arumugam, formerly of the Sri Lankan Educational service is a resident of Wellington for about fifteen years, a freelancer and has authored books on language, grammer, mathematics and Hinduism.

This publication is the result of a long time research, consultation and interviews which took him to various historical sites from Christ Church up to Whangarei in the north and has drawn conclusions from a diversity of authors, historians and academics such as Rubyn Gosset (New Zealand Mysteries), J.T.Thomson (The Whence of the Maoris), Ross Wiseman (Pre-Tasman Explorers) and John Crawfurd.

According to the author’s evidence, the bell was found after a shipwreck along the coast of Raglan, recovered in 1836 by William Colenso from the possession of the local Maoris whose antiquity is from Tahitian and Polynesian islands and was later exhibited in an exhibition held in Dunedin in the year 1862.

The author could be contacted at: [email protected]

He has drawn three conclusions as to how the bell – popularly called the Tamil Bell – reached the shores of this country. It may be from a shipwreck or brought by whale hunters or brought by Tamil traders.

According to his findings the Tamil lettering found on the bell and the Tamil lettering on the rock inscriptions of Weka Pass of Canterbury in Wellington and of Manu Bay, Raglan have similarities that gives credence to his conclusion that the Tamil Bell could have been brought by Tamil traders who were plying their trade in the Pacific area and the far east and could have been in the 14th or the 15th centuries.

His comparison also refers to similar Tamil inscriptions in China and Korea that are akin to those of New Zealand that could confirm his findings on the Tamil Bell.

This book of fifty-two pages could provide a good incentive for historians and researchers to go further deep into the migratory pattern of this multi-cultural country.

* * *

Further notes by TamilNet:

Presence of objective archaeological evidences such as the Tamil Brahmi inscriptions clearly testify early seafarers with definite Tamil identity reaching a wide region of the old world, ranging from Egypt in the West to Vietnam in the East, at least since the dawn of the Common Era, if not earlier.

Tamil Brahmi and South Indian Grantha of the early centuries of the Common Era are the earliest forms of alphabetic writing so far found in Thailand, Vietnam and in the Indonesian archipelago. Tamil inscriptions of the subsequent centuries as well as Tamil merchant settlements were found as far as in China.

Therefore, the possibility of Tamil navigators reaching New Zealand intentionally or by chance during the medieval centuries is not surprising, although discussions in the book are sometimes far-fetched in connecting the bell inscription with the engravings of symbols and paintings of the Maories or any other aborigines of New Zealand.

The symbols and paintings discussed in the book belong to a larger prehistoric heritage of Austro-Asiatic peoples ranging from the Veddahs of Ceylon to the aborigines of the Asia-Pacific region.

As West Asia and Arabs were having a long maritime connection with the ancient Tamil country, ever since the very advent of Islam the Muslims became naturalised into the Tamil heritage. Tamil was the earliest South Asian language adopted by maritime Islam as its lingua franca in the region.

During the medieval centuries, a Tamil-Muslim mercantile guild called Agnchuva’n’naththaar (Hagnjamana / Hagnjuman / Agnjuman in Persian or Arabic) was operating in South India, the members of which had Tamilized Muslim names, followed Tamil traditions and were issuing their inscriptions in Tamil.

(For updates you can share with your friends, follow TNN on Facebook and Twitter )