A provisional review:

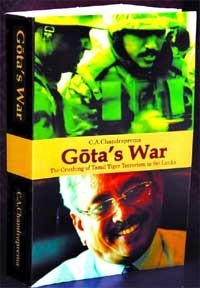

Gota’s War, a book by C A Chandraprema.

True to the tradition that the best is left for the last, the author of Gota’s War uses the last two pages of his rather bulky tome – 507 pages — for the most interesting anecdotal tale particularly in the context of the new developments concerning the Sri Lankan Tamil issue, post-Nandikadal. This is a juicy but goose-bump inducing recounting of political intrigue and low-level diplomatic subterfuge that goes as follows: Apparently, a high official in the US embassy approached Major General Prasad Samarasinghe at a US embassy party, called him to a side, and shoved a sheaf of papers in front of his face.

True to the tradition that the best is left for the last, the author of Gota’s War uses the last two pages of his rather bulky tome – 507 pages — for the most interesting anecdotal tale particularly in the context of the new developments concerning the Sri Lankan Tamil issue, post-Nandikadal. This is a juicy but goose-bump inducing recounting of political intrigue and low-level diplomatic subterfuge that goes as follows: Apparently, a high official in the US embassy approached Major General Prasad Samarasinghe at a US embassy party, called him to a side, and shoved a sheaf of papers in front of his face.

The document contained a list of ‘misdoings’ by Defence Secretary Goatabaya Rajapaksa among which were ordering of evictions from the city, covert operations etc.

Samarasinghe was then told that he and his wife would be granted permanent residency in the US, and that they would look after his son at a top US University if he signed these papers implicating his civilian boss.

Samarasinhge spilled the beans

A highly agitated Samarasinhge spilled the beans to Gotabhaya Rajapaksa next morning, and the US ambassador Butenis was confronted on the matter by the Defence Secretary the next day when she dropped by his office for a routine meeting. The narration continues to the effect that Butenis lied through her teeth saying that Samarasinghe had got into Wikileaks due to a US embassy “mistake’ and that since it was their mistake, they were only trying to help out the man, and not seeking to bribe him. How that entailed signing a document implicating Gotabhaya Rajapaksa for the litany of misdeeds committed during the war is never explained.

The author goes on to theorize that the formidable Tamil Tiger support mechanism worldwide that provided Prabhakaran backing for his war transformed into a lobby propagandising on alleged human rights violations of Tamil civilians, almost before Prabhakran’s body went cold by the Banks of the Nandikadal. Certainly it seems that no further proof is necessary to substantiate the author’s claim, after the events of early 2012, when our external affairs Minister was apparently ‘summoned’ to Washington by the US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

The book does not mince any words conveying the idea that the West (as always, read US) never forgave the Sri Lankan government for not doing that country’s bidding and stopping the military assault against the terrorists when the LTTE was in last gasp, pushed into a sliver of territory that was in military terms, the size of a postage stamp. For instance, some of the concluding pages of Gota’s War dwell on the IMF’s inordinate procrastination in the matter of transferring the monies pledged to Sri Lanka, to tide over a serious balance of payments crisis. Again, the West — (US) — was determined not to extend the facility, the IMF being under its control, and Hillary Clinton saying without seeing the need for any further elaboration, that ‘ this is not the time to’ dispatch the funds to Colombo.

If the lending-agency’s finances did not materialize, there would have been no choice but to stop the war as the economy would have collapsed.

‘Gota’s War’ narrative claims that eventually the Indian government gave an ultimatum to the US appointed mandarins at the IMF stating that if the money was not settled, India would come to the rescue by loaning the required amount courtesy of the Indian government. This was enough for those who called the shots including Hillary Clinton to back down and extend the facility, enabling the Rajapaksa government to complete the rout of the LTTE.

Obviously, this as other narratives before it confirms that behind Gota’s armed war, there were wars being fought on several fronts and at several levels, and there still are.

‘Gota’s War’ the book however, happens to be a far more comprehensive historical account of Sri Lanka’s campaign against rising Tamil militancy culminating in the ugly and almost interminable terrorist attacks of Velupillai Prabhakaran — and not a simple recounting of ‘Gota’s War’ only.

Its pages trace in parallel, Gotabhaya Rajapaksa’s career as a young Second Lieutenant in the Signals Corps, beginning in the early 1970s, with the tandem phenomenon of the rise of the Tamil armed movements in Sri Lanka with ‘disenchanted’ Tamil youth rising against the rabble-rousing federalist — and ultimately separatist — movement led by Chelvanayakam, the grumpy old man of Tamil politics, along with Amirthalingam, Sivasithamparam and others.

Though this analysis is certainly rather deep-going and absorbing in its own right, what the reader wants to get his teeth into obviously is the conduct of “Gota’s War’ after the LTTE carried out that now infamous act of sabotage of the rural agrarian economy by interdicting the waters of the Mavil Aru anicut in 2006.

Inside story

Chandraprema begins that account on page 321 – in the 520 page book — and certainly he does a very good job of walking the reader through the familiar terrain of Vavuniya to Vanni to Nandikadal, in the remaining pages.

Any reasonable local reader’s obvious knowledge of most of these recent events through the news coverage of the war as it happened cannot be discounted. What anybody would want under the circumstances is the inside story, and in giving a ringside view mostly through anecdotal accounts of key players, Gota’s War succeeds is giving this, the Sri Lankan side of the conflict — as much as Prabhakaran’s biographer Narayan Swamy succeeded in taking the reader beyond the cadjan curtain in his own account ‘Inside an Elusive Mind.’.

As stated at the beginning of this piece, this is a provisional review of sorts of this somewhat voluminous work, and this writer is quite certain there would be more faithfully detailed deconstructions to follow.

But, what appealed most to this reader of the book was the quirkiness of the anecdotage — meaning that some of the storytelling was fresh to the point of being hilarious — coupled with the fact that the author has a penchant for drawing out his own theoretical suppositions from parts of the narrative.

This is almost compulsive to the C. A .Chandraprema style, and there is certainly nothing that is objectionable about this particular peccadillo in writing for the historical record. But without attempting to detract from the quality of the work, it must be said that the reader begins to wonder how authentic or how realistic each theory is, while defending to the death the author’s right to give any kind of interpretation he wants to any issue that he considers pertinent.

For example, in the pre Mavil Aru chapters towards the beginning of the book, he castigates S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike for his decision to negotiate the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayagam pact and put his signature to it, saying that this kind of ill-conceived decision-making (devolving power to regional councils in the Tamil dominated north and east) gave the legitimacy and the prototype for the notion of Tamil separatism that subsequent Tamil politicians (mis)used. He goes to the extent of saying that this is not the way the Soulbury and Donoughmore constitutions were conceived because the British just said NO (capitals Chandraprema’s) to any kind of unreasonable demand.

But then, he had already said that 50-50 was the demand that the Tamil political leadership of the day, put forward to the British. Certainly, Bandaranaike himself would have absolutely said no to 50-50 as would have any other reasonable arbiter, and nobody would doubt that.

Inasmuch what the Tamils wanted from the British differed from what they wanted from Bandaranaike (i.e.: regional Councils) with or without a hidden ‘little now and more later’ motive, it makes the rationale that the quality of the leadership deteriorated from the astute British to the myopic Sinhalaese, a la Bandaraniake, rather a stretch.

There are many more theories on war politics and conflict that the author posits in this book and some are fascinatingly absorbing but sometimes quite confusing in logic as in the above example, as to seem to be rather quaint. I wonder what Gota himself may have made of all of this, but certainly anybody who wants to know more about his war might as well grab a copy without delay because as of now, this is the definitive work.

(For updates you can share with your friends, follow TNN on Facebook and Twitter )